Cockrell, Ellen (Nellie) Murphy

Gold Star Mother Memphis, Tennessee

- Description

- Grey Hair, Grey Eyes

- Born

- April 9, 1866

- Died

- August 14, 1933

- Occupation

- Housewife1

Introduction

Ellen, nicknamed Nellie, was born April 1866 in Memphis, Tennessee, to Jeremiah D. and Nettie Cockrell, both of Irish descent. Her husband, Davis, four years her elder, and she were married June 22,1885, by Father William Walsh at St. Brigid Catholic Church in Memphis, at Third and Overton. Between December 1886 and 1898, they had six children. Frank T. was born February 1896.2

To appreciate the full story of a Gold Star Mother, her story must include that of her son. Mary Ellen Cockrell was the mother of Private 1st Class Frank T. Cockrell.

Frank T. Cockrell

16351733513 Memphis, Tennessee

Frank enlisted in the army in 1917 and served with the 166th Ambulance Company No. 1, 117th Sanitary Train, 42nd Infantry Division.6 The sanitary train of each division consisted of train headquarters, an ambulance company section, a field hospital section, eight camp infirmaries, and a divisional medical supply unit. Three of the four companies in each of the ambulance and field hospital sections were motorized, the fourth being animal drawn.

42nd Infantry Division

The 42nd Infantry Division was the first full National Guard Division to sail overseas, representing many states and every section of the country.7 Tennessee’s contribution was the 166th Ambulance Company, one of four ambulance companies under Captain Percy A. Perkins of Memphis. 8 All personnel were sent to Camp Albert L. Mills, near Hempstead Village, Long Island, New York.9 By October 18, 1917, eight companies of more than 27,000 officers and men marched out the main entrance of Camp Mills to entrain at Garden City. Seven ships at the Hoboken, N.J. docks were awaiting their cargo, all German freighters with new American names. The “President Grant”, built in 1907 at Belfast, Ireland, for the Hamburg-Amerika Line, carried among its passengers, the Ambulance Section Headquarters, New Jersey and Tennessee Ambulance Companies and the Nebraska Field Hospital. At 3 a.m. on the morning of October 19, the transports began their voyage toward France.

President Grant

The third day out, the “President Grant” developed boiler trouble and began to lag behind. On the evening of the fourth day, it was decided that the “Grant” was unable to run the danger zone, and returned to New York. The remaining six transports would dock in St. Nazaire, France at the mouth of the Loire River on the morning of November 1, 1917. The “Grant” docked at Hoboken about 3 p.m. on the afternoon of October 27 and the troops were dispersed to neighboring camps. Tennessee was sent to Fort Totten, N.Y. where they remained for two and one-half weeks.

On the morning of November 14, 1917, personnel received orders to embark a second time for France, and the RMS Aurania and the White Star Liner Celtic ships put out to sea around 3:30 p.m. Ambulance Section Headquarters, New Jersey and Tennessee, embarked on the RMS Aurania at Pier 56.

With a stop in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on November 16 and Belfast, Ireland, on Thanksgiving Day, they anchored in Liverpool, England at 1:00 a.m., December 1 and marched to the railway depot. The train pulled out for Camp Wendledown, Winchester with a stop in Birmingham.

A story is told of a distinguished older Englishman and his wife, both gazing curiously at a group of American soldiers. They finally asked: “What province are you from?” “No province sir,” answered the boys. “We are Americans.” “Indeed,” said the woman, “and what part of the United States is your home?” “We are Tennesseans from Memphis to be exact,” was the answer. “Ah, how singular,” she exclaimed. “I have been in Memphis but I never knew that Tennessee had declared war.” They departed, leaving the national guardsmen wondering whether the lady had been on the banks of the Mississippi or the Nile when she was in Memphis.

Somewhere in France

On December 11, Ambulance Section Headquarters, New Jersey, Tennessee and Nebraska, left Camp Wendledown for Southhampton and crossed the English Channel on the “Marguerite.” Once arriving at La Havre, they entrained for La Fouche on December 13, arriving two days later. Tennessee was housed in the town proper, in shacks more or less dilapidated, and entirely lacking in conveniences and heat.10

Upon leaving the village in eight inches of snow, Ambulance Section Headquarters, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Nebraska, hiked under a sixty-pound pack. Letters from home served a dual purpose by inserting them in their shoes to keep their feet off the ground. By 10 a.m., the soldiers had reached St. Blin and the complete train was once more together for the first time since leaving Camp Mills. They continued their trek through Remicourt, Echo, Mandres and Nogent-en-Bassigny in blizzard conditions with temperatures below zero. Only local oxen could pull their loads up hills. By noon on December 29, the ambulance men had reached their destination in the village of Rolampont, where 42nd Division Headquarters was already situated. 11

In early January, it was decided that Michigan should go motorized, and Tennessee should be the animal-drawn ambulance company of the train. They did all the hauling for the section. The twenty-four Fords began to deteriorate and no spare parts could be had in France. By the end of January, the ambulance park was a junk pile.

Orders came to prepare for a trip to the trenches, a training trip. Desire for excitement to break the monotony of camp routine overran their every emotion.

Just after February 17, 1918, a narrow-gauge, French locomotive, pulled out of Rolampont with the sanitary train, men packed forty in a train car, cramped and cold. They spent that night and the next on the cars. About midnight of the 19th, Tennessee and New Jersey who were on the second section of the train, were permitted to unload at the station of the demolished town of Gerberviller. The other five companies, traveling a few miles ahead, had taken siding between sundown and dark, in the town of Moyen, Meurthe-et-Moselle. They had orders not to wander away from the train when they got out, and it was while waiting along the track there, that they learned that someone had made a mistake. They were not supposed to be in Moyen at all. While they were sleeping, Tennessee and New Jersey had unloaded at Gerberviller, had eaten a light lunch and struggled under packs for a distance of twenty kilometers through the dark, arriving in Loromontsey at daybreak. By 9 a.m., the troops in Moyen had eaten and started out again toward Gerberviller.

They were marching over the first battlefield they had ever seen. The battlefield was three years old and the present lines were far away. They observed French observation balloons off to the northeast. Little wooden crosses stood in groups of twos and threes at regular intervals along the meadow. After 1 ½ hours, the first ruins of war came into view in the city of Gerberviller. Earlier in the war, the horse of a German general had been shot out from under him, and in return he ordered that no building be left standing. They ate lunch with the French who were rebuilding the city while on leave from the trenches. Tennessee and New Jersey had arrived early in the morning in Loromentzey, so they had a hot meal waiting for the incoming troops.

The second night offered an opportunity to see the lights of the firing line. The cannons of the French were plainly audible and one could see the torches of no-man’s land. The hospitals began to move forward on the 21st of February to support the French. The day after Washington’s Birthday, the ambulance men were inspired by the sight of a long convoy of G.M.C. ambulances coming down the road toward Loromontzey. Jersey, Oklahoma and Michigan companies were each issued twelve new ambulances, two Pierce Arrow trucks and Dodge touring cars for the officers. Tennessee proceeded with ambulances and wagon train to Moyen, where they raised to full strength their animals while being held in reserve. The other three companies were sent to the front to get their “baptism of fire.”

Tennessee Nine

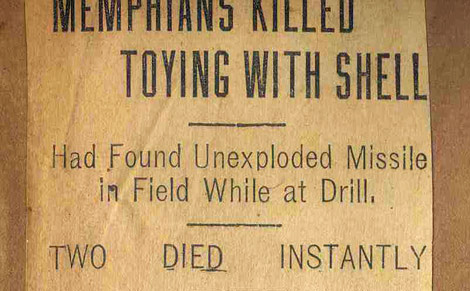

Tennessee would soon suffer more loss than all the companies in the trenches combined. “A party of her men, out walking over the old battlefield near Moyen, picked up a “77” dud, and brought it into camp. A few days later (March 7), while some of the men were playing at shot-put with the harmless-looking projectile, it exploded, resulting in the death of nine men and the life-time disfigurement of another.

Commercial Appeal Article.

March 12, 1918

Commercial Appeal Article

Corporal George S. Sanford, Privates Joe D. Brakefield, Thomas G. Bragg, Frank T. Cockrell, Willie J. Hayes, Roy G. Hovey, Edwin L. Fitch, Fred R. McGill and John J. Brannon, Jr., died within twelve hours. Frank would be buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Monfaucon, France, once the many temporary burials were brought together after the war. Private James W. Brown survived with the loss of one leg and the impaired use of other limbs.

Tennessee Nine - Original Burial

Besides the men who were lost, the explosion played havoc with the picket line, killing several mules. Except for this catastrophe, Tennessee’s stay at Moyen was uneventful. 12

Tennessee would go on to distinguish itself in the Champagne Region, Chateau Thierry, St. Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne fronts on their way to Sedan. Towards the end, American divisions were so eager to be first into Sedan that they actually captured Brigadier General Douglas A. McArthur of the 42nd in their rush, holding him as a suspect until he established his identity. The war ended on November 11 and the 42nd became part of the Army of Occupation of Germany. 13

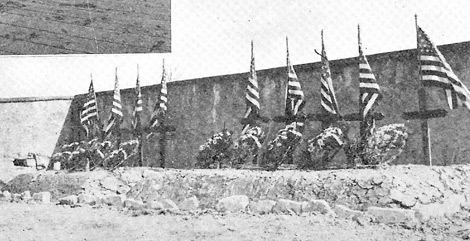

Frank as well as all the men and women who gave their life from Shelby County, Tennessee are listed on the base of the Doughboy Statue in War Memorial Plaza in Overton Park, Memphis, Tennessee. 14

Doughboy Statue in Overton Park (Veterans Plaza)

Sculptor Nancy Coonsman Hahn

Erected September 21, 1926.

The Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages Of 1930 - 1933

At the time of the Armistice there were approximately 2,400 places in Europe where American dead lay temporarily buried. 15

At war’s end, many argued that the war dead should remain interred overseas as a symbol of U.S. commitment to Europe. In 1919, Secretary of War, Newton Baker, offered family members the opportunity to make the final decision on whether they wanted their next of kin to remain in France, or be brought home for internment in a national cemetery, or family plot. Seventy percent chose to have their loved ones returned to the United States for burial.

By the Armistice of November 11, 1918, there were more than 75,000 American war dead, and of those, approximately 31,000 would forever lie buried in U.S. Cemeteries overseas. For those to be buried in Europe, eight permanent American cemeteries were established by the War Department. 16

The American Battlefield Monuments Commission was established by Congress in 1923, as an agency of the Executive Branch of the Federal Government, a guardian of America’s overseas commemorative cemeteries and memorials.17

In March 1929, eleven years after the war, the U.S. Congress passed a law authorizing the use of government funds (5 million dollars) to pay for mothers and widows of fallen veterans to visit their loved ones buried on the battlefields of Europe. 18 On May 6, 1930, the S.S. America steamed out of Pier 4 from Hoboken, New Jersey, the same pier where thousands of soldiers attached to the American Expeditionary Forces had sailed to participate in the Great War. All 231 women aboard, including 56 of foreign birth with the majority claiming Germany, were guests of the U.S. Government. 19 The cost to the government was $840 per person. There were 11,440 mothers or widows entitled to make the pilgrimage, and 6,730 expressed a desire to go. 5,323 women would make that trip in 1930 and Nellie Cockrell would be one. 20 Over the next three years, ending with the return of the S.S. Washington in August 1933, some 6,693 Gold Star Mothers and War Widows had made the pilgrimage abroad to American cemeteries in France, Belgium and Great Britain. 21

These voyages were known as The Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages of 1930 -1933. They offered loved ones an opportunity to come to terms with grief and find the sacred in a shared experience.

Gold Star Mothers derived their name from the star they displayed on service flags in their homes during the war. The blue star flag showed that the household was home to a fighting man, but mourning the loss of a son or husband was typically accompanied by the mourning dress of the period. As casualties grew, so did the concern that these deaths would have a negative impact on public morale. President Wilson asked for suggestions for an alternative to the traditional black wear, and the idea of a gold star on an armband of black cloth won endorsement in 1918. Later a gold star on a service flag represented a son killed in war service and brought praise to women for their sacrifice. 22

Nellie’s Voyage To France

As a Gold Star Mother, Nellie Cockrell received a letter as she was the relative or person who authorized Frank’s burial in the cemeteries of Europe, now interred there. The United States Government Printing Office in Washington created House Document No. 140 for the 71st Congress, 2nd Session titled PILGRIMAGE FOR THE MOTHERS and WIDOWS OF SOLDIERS, SAILORS, and MARINES of the AMERICAN FORCES NOW INTERRED in the CEMETERIES of EUROPE AS PROVIDED BY THE ACT OF CONGRESS OF MARCH 2, 1929.23

Nellie was identified as Frank’s mother living at 462 Mosby St., Memphis. Desires pilgrimage? Yes.24

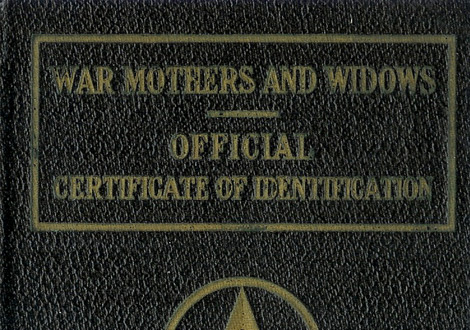

The U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps took charge and led these pilgrims on a month-long trip. Nellie was given two passports: one the Official Certificate of Identification (Serial No. 3338) for War Mothers and Widows and the second a U.S. Passport (No. 3000).

War Mothers and Widows Passport

Within the pages of her passport, Nellie had written the name and address of a fellow traveler, perhaps a person with whom she shared her grief. Mrs. Flora M. Vilott, 35 years of age, was from Burr Oak, (Jewell County) Kansas and the widow of Pvt. Fletcher L. Vilott, Co. G, 355th Infantry, 89th Division, who also was buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery. Flora, a young wife, was only 24 years of age at the time of the Armistice.

U.S. Passport

Nellie’s passport was stamped at Cherbourg, August 27, 1930, upon arrival and again on September10 upon leaving, a total of 15 days inclusive. The voyage took a total of 10 days each way making the whole trip approximately one month. 25

Arrangements for a typical war mother began with acceptance of the government’s invitation to make the pilgrimage. Nellie received a letter making suggestions as to the advisability of taking clothing that is simple in style and of medium weight and warmth, comfortable walking shoes, a warm coat and a pair of overshoes. Two pieces of baggage could be taken not exceeding 100 pounds. The travel arrangements included dates and times of travel, as well as berth, seat, or room number for the ship, trains, and hotel rooms.

Nellie first traveled by train to New York and her Gold Star Mother’s badge provided her identity to all those assisting her. She would rest in New York for two days.

Gold Star Mothers Badge

A War Department representative provided Nellie and the others the necessary transportation and escorted them to the pier and onto the boat. All the pilgrimages were scheduled between May and September to accommodate the comfort of the travelers to the most pleasant sailing season of the year. The boats were part of a fleet owned and operated by the United States Lines, an American corporation. Every attempt was made to have mothers and widows of the same state travel together.

All those visiting the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery disembarked at Cherbourg and assembled into smaller units of 25 each, traveling to Paris by rail26, entraining at Les Invalides (usually reserved for state occasions), to avoid the congestion of the St. Lazaire Station. First class hotel accommodations were provided at the Hotel Imperator, rue Beaubourg, double rooms with twin beds and a bath.

After a day of rest, Nellie’s group would select an “honor pilgrim,” who laid a wreath on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Arc de Triomphe. Following a tea and reception in their honor, the women were free to see Paris before departing for the countryside the next day.27

Each group proceeded by motor bus to a small town in the vicinity of the cemetery to be visited, a temporary headquarters for the next seven days. The quartermaster built, within ninety days, rest houses at each of the cemeteries. The rest houses had tables, comfortable chairs and restrooms as well as kitchen facilities and a shady porch. The women viewed points of historical interest as well as battlefields where American troops were engaged. All the cemeteries where American troops are interred are on ground captured by American troops. On Frank’s marker, Nellie found inscribed there her son’s name, rank, organization, State and the date of his death.28 The Army provided each woman a wreath of flowers, a photograph of her at the grave, and plenty of time alone.29

Upon completion of the program at the cemeteries, Nellie and the others were taken back to Paris, where for five days; they were afforded an opportunity to visit more points of interest. Upon conclusion of her stay, Nellie was provided transportation from Paris to Cherbourg where on September 10th she sailed on the S.S. America steamer for the port of New York. She was then furnished a railroad ticket back to Memphis.30

NELLIE’S DEATH

Frank died at 22 years of age and was buried in France on March 8, 1918. Davis, Nellie’s husband, an engineer with Tennessee Fiber Company, would die on May 19 of the following year with pulmonary tuberculosis at 56 years of age.

Nellie lived to bury her husband, and visit her son’s grave in France before her own death on August 14, 1933 at 3:12 p.m. She was buried the next day at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, just south and east of its entrance. The principal cause of death was pernicious anemia, a decrease in red blood cells.31 A simple gravesite (Turley Plot, Lot 569, #13) marks where both she and Davis are buried. Their daughter Margaret Gallagher, her husband and children are buried nearby.32

SUMMARY

Frank T. Cockrell made the supreme sacrifice in the First World War and his body remains in the soil of France, the choice of approximately 31,000 families. Gold Star Mothers fought an 11 year battle, through four presidential administrations, for a bill signed by President Calvin Coolidge in 1929. The bill authorized the use of government funds to pay for mothers and widows of fallen veterans to visit their loved ones buried on the battlefields of Europe. Between 1930 and 1933, approximately 6,693 women such as Nellie said goodbye to their sons, looking for a way to find peace in their lives.

On your next visit to the Western Front, and in particular, the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, follow Nellie’s footsteps and you will find her son Frank, in Plot D, Row 10, Grave 25.33

Do you know more about this person? Click here to email the author.

References

- War Mothers and Widows Pilgrimage Official Certificate of Identification Serial No. 3338, Mrs. Nellie Cockrell

- List of Mothers and Widows of American Soldiers Sailors and Marines Entitled to Make a Pilgrimage to the War Cemeteries in Europe, United States Government Printing Office, 1930, p. 292

- Ancestry.com, Ellen (Nellie) Cockrell Murphy

- American Battle Monuments Commission, Frank T. Cockrell

- Ancestry.com, Ellen (Nellie) Cockrell Murphy

- American Battle Monuments Commission, Frank T. Cockrell

- Associated Staff, Iodine and Gasoline A History of the 117th Sanitary Train, 1919, Bad Neuenahr, Germany, p. 1

- Ibid, p. 7

- Ibid, p. 6

- Ibid, p. 15-37

- Ibid, p. 39-43

- Ibid, P. 48-56

- Ibid, p. 121

- http://www.arkansasties.com/OtherStates/Tennessee/World War1.htm,

- David W. Lloyd, Battlefield Tourism, (Oxford: Berg, 1998), p, 114

- Lisa Budreau, ‘Morning and the Marking of a Nation: The Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages, 1930-1933’, April 2002, p. 3-4

- American Battle Monuments Commission

- http://www.qmmuseum.lee.army.mil/historyweek/5-11feb.htm, Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages – 1930-1933, Quartermaster History This Week

- Lisa Budreau, April 2002, p. 3-4

- List of Mothers and Widows of American Soldiers Sailors and Marines Entitled to Make a Pilgrimage to the War Cemeteries in Europe, 1930, iii

- http://www.qmmuseum.lee.army.mil/historyweek/5-11feb.htm

- Lisa Budreau,, April 2002, p. 3-4

- List of Mothers and Widows of American Soldiers Sailors and Marines Entitled to Make a Pilgrimage to the War Cemeteries in Europe, 1930, iii

- List of Mothers and Widows of American Soldiers Sailors and Marines Entitled to Make a Pilgrimage to the War Cemeteries in Europe, 1930, p. 292

- Collection of Andrew Pouncey

- Major Louis C. Wilson, Q.M.C., The War Mother Goes “Over There”, The Quartermaster Review, May-June 1930

- World War 1 Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages, Park II, Constance Potter, Prologue Magazine, Fall 1999, Vol. 31, No. 3

- Major Louis C. Wilson, Q.M.C., May-June 1930

- World War 1 Gold Star Mothers Pilgrimages, Part II, Fall 1999, Vol. 31, No. 3

- Major Louis C. Wilson, Q.M.C., May-June 1930

- State of Tennessee, Certificate of Death, Mary Ellen Cockrell

- Elmwood Cemetery, Memphis, TN

- American Battle Monuments Commission, Frank T. Cockrell

Image Credits

- The Collection of Andrew Pouncey

- The Commercial Appeal - March 12, 1918

- Naval History & Heritage Command Web Site – U.S. Navy Ships

- U.S. Official Pictures of the World War Showing American Participation by William E. Moore, Late Captain, U.S.A. and James C. Russell, Late Captain, U.S.A., 1920, p. 84

- The Commercial Appeal – March 12, 1918

- Iodine and Gasoline A History of the 117th Sanitary Train, 1919, p. 142

- American Battle Monuments Commission Web Site

- American Battle Monuments Commission Web Site - Video

- WW1 Memorial, Memphis, TN: Challenges: Digital Web Site - Doughboy Statue

- The Fenelon Collection

- List of Mothers and Widows of American Sldiers Sailors and Marines Entitled To Make A Pilgrimage To The War Cemeteris In Europe, 1930, p. 292.

- The Collection of Andrew Pouncey

- Pouncey

- Pouncey

- Pouncey

- Pouncey

- American Battle Monuments Commission

- The Fenelon Collection

- The Collection of Andrew Pouncey

- Pouncey

- American Battle Monuments Commission